Negative advertising is rampant in today’s political process. Whether at the national, state, or local level, campaigns create advertisements that attack and create unfavorable opinions of their opponents. In order to detract voters from their opposition, campaigns attempt to negatively define their opponent before that candidate has a chance to define themselves in a positive light; they do this with negative ads. After defining a negative ad, scholars and politicians alike have questioned the memorability of negative versus positive ads and whether or not these destructive advertisements succeed in drawing support away from their opponent. Politicians also worry about the backlash the aggressive ads might have on their own campaign and their success.

Negative advertising is rampant in today’s political process. Whether at the national, state, or local level, campaigns create advertisements that attack and create unfavorable opinions of their opponents. In order to detract voters from their opposition, campaigns attempt to negatively define their opponent before that candidate has a chance to define themselves in a positive light; they do this with negative ads. After defining a negative ad, scholars and politicians alike have questioned the memorability of negative versus positive ads and whether or not these destructive advertisements succeed in drawing support away from their opponent. Politicians also worry about the backlash the aggressive ads might have on their own campaign and their success.

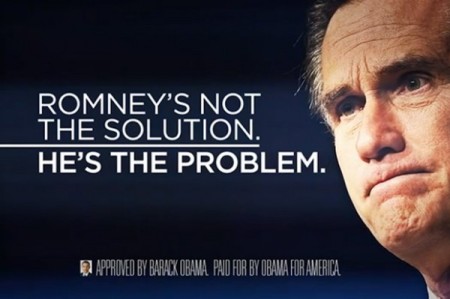

Ads are only classified as negative if they focus on “degrading perceptions of the rival, to the advantage of the sponsor.” Otherwise, they may just be comparative ads. Comparative and negative ads both clearly identify who they are targeting, but comparative ads only persuade people if a non-comparative ad is seen as well (Merritt). While comparative ads might mention characteristics of the opposing candidate, negative ads usually do not identify any at all but instead attempt to make the opponent seem like the worse candidate. Negative ads play off of the opponent’s gaffes and bring up any blemish on their record or in their history. In order to make an impact in the political race, campaigns rely on advertisement memorability.

Studies have shown that voters are more likely to remember ads that are more severe, rather than moderately negative ones (Merritt). Attack ads are noticed and processed more easily and, therefore, are remembered better than supportive ads; thus, the more aggressive the attack ad, the more likely people are to remember it (Thurber). Based on this conclusion, in order to be the most memorable, campaigns should make their ads more destructive than those of their opponent. However, producing negative ads may also harm the candidate’s reputation. The high memorability of harsh negative ads contrasted with the threat of deterring voters with ads that are too aggressive creates a struggle in political campaigns about how negative their ads should be.

In order to successfully attract support away from their opponent, campaigns should only use negative ads in two party races (Merritt). The only time they guarantee to draw the opponent’s supporters to their own party is in a bipartisan race when the voter has to choose between the two candidates. However, even in these situations, there are no guarantees that voters will swing their support from one candidate to another just because of a commercial.

Researchers are divided over whether or not negative ads are effective or hurtful towards the campaign that produces them; however, one experiment concluded that, overall, citizens do not like negative advertising. Comparative advertisements may cause adverse attitudes toward the opponent, but also cause cynicism toward the product that produces the ad. This pattern occurs in negative advertising as well (Thurber). Listeners and viewers become annoyed with both sides of the campaign and dislike all negative ads, no matter the producer. Their unfavorable views of the ads may cause them to be less likely to participate in the election.

There is a growing rift in campaign advertising; negative ads are more memorable than their positive counter parts, but citizens do not like them and are deterred from the electoral process because of their prevalence. Campaigns must decide how to deal with this fissure. Do they produce harsh destructive advertisements and risk deterring citizens from voting at all, or do they scale back on their negative ads and risk being adversely defined by their opponent? In today’s political campaigns, about one third of the commercials in political campaigns today are negative ads, and now that PACs and businesses are allowed to freely support a candidate, this fraction is rising. In addition, ads created by interest groups are more extreme and harsh than the ads created by the candidate’s campaign itself (Merritt). While the amount of negative ad buys has increased in recent elections, voter turnout has declined. It is not clear whether this is correlation or causation, however, ads are becoming increasingly important to elections. It will be interesting to see how future campaigns balance the need for negative ads without tipping the scale in their opponent’s favor by producing too many and discouraging their own voters.

Sources

Merritt, S. (1984). Negative Political Advertising: Some Empirical Findings. Journal of Advertising, 13(3), 27–38. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/4188512.pdf

Thurber, J. A. (2000). Effectiveness of Negative Political Advertising. Crowded Airwaves: Campaign Advertising in Elections (pp. 10–27). Brookings Institutiong Press. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=OzONzuQOSskC&oi=fnd&pg=PA10&dq=negative+political+advertising&ots=D4QxXVn42G&sig=W-yMGNh4JhqNRAGKfmGSxW1VADQ