The chorus of the media’s most strident detractors sings with an accusatory accent, harmonizing with unequaled resonance when it appears the “liberal media” have done it again. Those tree-hugging marauders have stifled conservative thought with a bias so satanic that it jeopardizes the health of democracy. That’s a sophomoric embellishment, of course. But hyperbole or not, those decrying a purported cliffside-slant in the media have never wailed louder.

Timothy Cook discusses the genesis of bias in “Governing with the News: The News Media as a Political Institution.” He points not to ideological preferences or latent agendas of unadulterated liberalism, but rather the routinized modus operandi of journalists that cajole bias out of their otherwise objective stories. Cook, then, has a firm grasp on why bias might occur in the press. But he begs the question without addressing it:

Is there a bias?

That’s the cause that Gerard Matthews takes up in his 2009 essay “Bias” in the Encyclopedia of Journalism. He argues, rather effusively, that any claims of systemic media bias appear unfounded. But Matthews, in an admiringly measured tone that schools MSNBC and Fox in the concept of rational thought, explores the underpinnings of other sources of subjectivity in media — most of which have little to do with a journalist’s sympathies for elephants or donkeys.

Matthews first invokes Robert Entman’s work “Framing Bias” to discuss how the media imparts the prioritization of specific issues to the public: Issues that receive considerable coverage garner, by extension, considerable attention from the public, which assumes that the press coverage connotes an issue’s heightened significance (Matthews 159). But the public’s receptiveness to the media’s nudge toward certain stories relies on “cultural congruence,” or how closely an issue aligns with the public’s worldview. The state of the economy makes for a successful media frame. The newly passed farm bill? Not so much.

Bill and Hillary Clinton learned this the head-banging way in 1993 during their ardent push for healthcare reform. The Clintons championed their plan as a means of uplift for the poor, a mechanism of redistributive Pollyanna that would deliver the American Dream to the doorsteps of the downtrodden. The message made Democrats swoon. Meanwhile, it made others recoil: It was incongruous with the libertarian inclinations of a sizable portion of politicians and voters (Matthews 160). An inadequate frame did the Clintons no favors in a policy fight that they would ultimately lose.

While framing endures unabated, bias does not: Matthews cites abundant evidence quashing fatalistic warnings of a “liberal media.” Among them:

1) Entman noted some researchers who found a conservative media bias in coverage of some issues, namely social movements, the tax policies of labor unions and — with unmistakable irony — coverage of media bias itself.

2) In a 1992 study, James Kuklinski and Lee Sigelman deemed media coverage of U.S. senators satisfactorily objective.

3) Dave D’Alessio and Mike Allen released a 2000 study that revealed a marginal bias in TV network news toward giving Democrats slightly more airtime — though as Matthews writes, sometimes no press is better than bad press.

4) A Yale study found that Washington Post subscribers were substantially more likely (eight percentage points higher) to vote for the Democratic candidate in the 2005 Virginia gubernatorial race (Matthews 158-159). That alone doesn’t suggest bias, of course: The Post has long had a more liberal readership. It’s analogous to saying that loyal Fox News viewers were markedly more likely to vote for George W. Bush in the 2000 and 2004 elections. It’s doubtful that scenario would give anyone a coronary about the outsize influence of the perilous “conservative media.” In the case of The Post and Fox, it’s nothing more than political partisans eating at their favorite troughs.

What fuels this faulty perception of media bias, then? Perhaps it’s simply the boys and girls who cried “wolf.” The acclaimed political communications researcher David Domke said in a 1999 study that the prevalence of the “liberal bias” theory resides not so much in the growth of liberal coverage but rather the profusion of media professionals and consumers lamenting the dubious presence of a liberal bias. In reports of media bias from the 1988, 1992 and 1996 presidential elections, Domke found, 95 percent of them referred to a liberal bias (Matthews 159). The media didn’t beat the dead horse of the liberal media narrative so much as they bludgeoned it into the crust of the Earth.

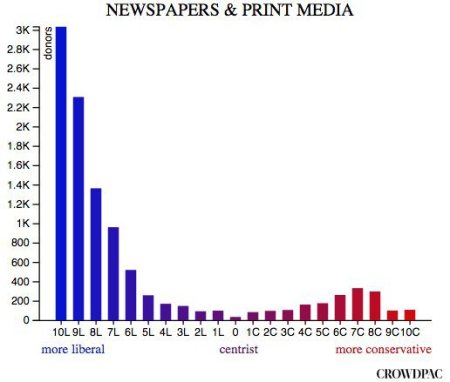

Could it be the professionals themselves? Yes, says former CBS reporter Bernard Goldberg in his book “Bias.” Goldberg wrote that media professionals are overwhelmingly liberal, particularly on social issues, and their constant fraternization with their journalistic peers often leads to liberalism by osmosis — or, at the very least, the reinforcement of liberal values. “They see [conservatives] as morally deficient,” Goldberg wrote, sounding like a paranoid, staunch conservative, most likely because he is a staunch conservative (Matthews 160). Sarcasm aside, Goldberg raises a legitimate argument. In a 2014 study, Crowdpac, a non-partisan political data analysis firm, pored over 30 years worth of campaign finance records and organized them by profession. It found, much to the delight of conservatives, that donors who worked for newspapers and other print media were disproportionately liberal.

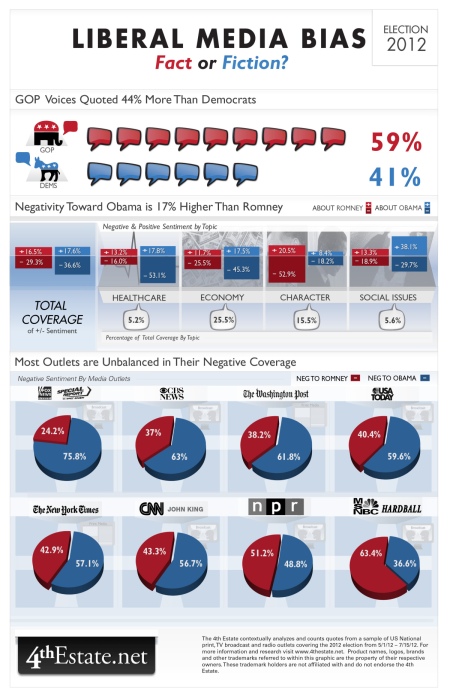

Yet while most reporters, copy editors and photographers lean liberal, does their coverage, too? Not quite, says the 4th Estate, a media data company. In an analysis of the 2012 presidential election, 4th Estate found the media quoted Republican advocates more often (44 percent more than Democrats) and covered Barack Obama more negatively than Mitt Romney (17 percent more). And perceived bastions of liberal politics, namely the New York Times and the Washington Post, devoted more negative coverage to Obama (57.1 percent and 61.8 percent) than to Romney. Of the eight outlets surveyed, only two — NPR and MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews” — lent Obama more favorable coverage than Romney.

That’s precisely why Matthews views accusations of media bias with fervent skepticism. Some journalists, he writes, are so sensitive to upholding objectivity that they sometimes sublimate their own personal views and adopt an opposing viewpoint to avoid the appearance of bias. Sometimes, Matthews writes, a story has more than the obligatory two sides and is more kaleidoscopic than black and white. Sometimes the claims of one side of the story are grounded in reality and fact while the other side boasts a casual relationship with the truth. And sometimes time and resources, not bias, emerge as the chief inhibitor to fully balanced journalism. Deadlines and financial constraints allow for only so much reporting, which invariably forsakes a piece of an angle or a key opposing actor (Matthews 160).

Yet Matthews doesn’t completely absolve the media. He needles them for its “game frame,” or the media’s penchant for breathlessly covering political maneuvering and strategizing — the “game” — at the relative exclusion of discussing pressing policy issues in a thoughtful, meaningful capacity (Matthews 161). This infatuation with politics as a chess set or football field does little to help the public’s confidence in government: Joseph Cappella and Kathleen Hall Jamieson posit in their book “The Spiral of Cynicism” that the media’s emphasis on the sports-style operations of the political machine stokes feelings of disillusionment and powerlessness among voters, who often feel removed from the political players and the manipulative games they play (Matthews 161). Regina Lawrence perfectly encapsulates the crime of obsessing over the game of politics: “News organizations are most likely to approach the political world with the superficial and cynical game schema at precisely those times when public opinion is most likely to be formulated, mobilized and listened to by politicians: during elections and highly consequential legislative debates” (Matthews 161). When the media have the chance to do the most good, it often does the worst.

But Lawrence also argues, rather misguidedly, that the “game frame” allows journalists to more deftly walk the ideological tightrope while stiff-arming the task of covering complicated policy issues that would require extensive reporting and research (Matthews 161). Not so fast: Most coverage directives come from editors, and editors know that political intrigue, not the minutiae of policy, sells papers and lures clicks. That’s precisely why Hillary Clinton’s email kerfuffle has received as much airtime as it has — a full 20 months before the next presidential election. It’s not a matter of journalistic laziness: It’s a practical recognition that drama sells.

Matthews closes with a pie-in-the-sky hope for the future of media: “Media coverage of important policy issues or legislative debates should reflect, as much as is possible, the empirical evidence, instead of ensuring that dueling ideologies are equally represented irrespective of their own support or validity” (Matthews 162). In non-pretentious speak: The facts, not balance, are imperative to exemplary reporting. Report the truth, and nothing but the truth, even if the truth only extends to one side of the story. So help you God.

How quaint. But it’s almost impossible to be heard over the roar of the chorus.

____________________________________________________________________

Works Cited:

Matthews, Gerard. “Bias.” Encyclopedia of Journalism (2009): 158-162).

“These Charts Show The Potential Bias Of Workers In Each Profession.” Crowdpac via BusinessInsider.com.

(http://www.businessinsider.com/charts-show-the-political-bias-of-each-profession-2014-11)

“Why The GOP Can’t Use ‘Liberal Bias’ As An Excuse Anymore.” The 4th Estate via Upworthy.com.

(http://www.upworthy.com/why-the-gop-cant-use-liberal-media-bias-as-an-excuse-anymore).